Coaches regularly go on a rant about their game plan. It is often not as clearly communicated with their players or as well laid out as it should be. Putting together a game plan involves more than just having some general ideas in your head.

Your worst enemy is using generalizations. Saying to your players you want them to “play running rugby” or “play the situation in front of them” gives them very little to go on. You are bound to very rarely get the results you actually want from them if you don’t give them more to go on.

The success of putting together a game plan is in planning. If you do proper planning and have it laid out, you will be able to relay it a lot more clearly to your players. The players need to understand it and need to know what you envisage right at the start of the season.

If they don’t know what you are trying to achieve, they won’t understand why you are doing specific skills drills every week. If they are clear on the vision, you can tie in the respective drills to what you want to achieve on the field and the connection would make sense to them.

VERY IMPORTANT TO NOTE: Coaches love a game plan and want to put their stamp on every team that they coach. As a coach, you need to remember that every game plan doesn’t work for players of every age. The simple rules to go by is:

- no game plan at all for players under 10

- extremely simple and basic game plan for players between 10 and 14

- simple game plan for players between 14 and 18

- full game plan for players over 18

General ideas around putting together a game plan

If you allow yourself to really get stuck into it, you will probably be able to put together a monster of a game plan that covers every possible scenario. That is however almost never the right approach.

Here are the general things you should consider:

- Keep the whole plan to less than 1 page – you need to be able to relay it to players quickly and concisely. It should always be the same message and make 100% sense to them

- Keep it simple – don’t try and address every single aspect of the game. If you are not in a professional set up where you get to work with the players about 40 hours every week, you will not be able to implement a complicated game plan. Focus on a handful of key areas that you would like to deliver on

- Have measures of success (KPIs) – you want to know after every game if you were successful in executing your game plan or not. This is where video and stats become your friend. Keep tabs on how many of the intended actions were executed successfully. If you get more and more effective as a team in these mini battles in games, you will win more games

Specific areas that should be addressed in a game plan

It is often difficult to limit yourself as a coach in your game plan and not go totally over the top. As the game is very dynamic and changes from one phase to another you need to rather focus on:

- What players should do in specific areas of the field

- What players should do based on the state of the game

A lineout, scrum, backline move or penalty move is only as good as where and when it is executed.

There areas you need to address in a rather simple manner is your own 22 (defending), the opponents 22 (on attack) and then the rest of the field.

When you are in your own 22

What you do in your own 22 becomes a critical part of whether you will win the game or not. It might sound strange, but the effectiveness and accuracy of your defense will win you most games.

Sir Graham Henry famously said that “defense wins championships”. There isn’t really any reason to argue with a legendary All Blacks coach of his stature. He had the luxury to ONLY focus on rugby for a few decades, so he had enough time to thoroughly analyze it and think it over.

There are two basic areas you should focus on. Both of them are conservative ideas and easy to execute, but teams are often undone when they can’t cope with the pressure.

The two areas to focus on is:

- When you don’t have the ball in your own 22

- When you have the ball in your own 22

When you don’t have the ball in your own 22

The key to success when playing without the ball is to have patience and continued concentration. You need to make sure that you do the following things repeatedly:

- form a solid defensive line as quickly as possible (and quickly after every phase)

- make your tackles – the more you can make in pairs, the better

- try and steadily move the attackers away from your goal line with a coordinated rush defense

If these three are repeated phase after phase you will eventually force the attackers into a mistake and force the turnover. The further you move them away from your line, the quicker the risk percentages drop.

When you have the ball in your own 22

If you have turned the ball over you have won a huge battle. This is however not the time for rash decisions. It definitely looks amazing if you turn the ball over and run it back 80m or 90m for a try. It is however not worth the risk in most instances.

The better option is to slow things down as much as possible. Put together the safest possible phase in the form of a ruck, lineout or scrum. Make it safe for you 9 or kicker in the pocket to get you out of your 22.

The first goal is to get out of your 22. Just kicking downfield is not the answer as you are not set on defense and you can be exposed with a counterattack. You need to get the ball out. So the kick must get out of the 22 and into touch.

A simple exit like that is not spectacular to watch, but it is a victory for your players. They defended their goal line and defeated the attackers. It is a mini-battle won.

When you get into your opponents 22

Your biggest ally is the nervousness of your opponent’s defense. You want to fracture their defense and there are two ways that this gets done:

- create mismatches – forwards running against backs or backs running against forwards

- moving the ball across the field at speed

The principles behind both ideas are relatively simple to do. They require patience, focus and an increase in intensity to execute successfully.

Creating mismatches

Mismatches on the field almost result in territory gains for a team. When you have a forward running against a back the forward often has a size, weight and strength advantage. The back might bring them down, but often only after the forward has gained at least a meter or two.

The reverse of a back running against a forward comes down to beating your opponent with speed and agility.

When you have a lineout or scrum, you will not have these mismatches. Here you need to rely on moves that you practiced to get over the advantage line. Mismatches are created from rucks.

Here are a couple of random ideas that you can build on:

- running pods of forwards off your 10 or 12 at the opposition backline

- putting a wing in at 9 at rucks close to the line (they can normally step around the forwards in the ruck)

Once the first mismatch is created it is very difficult for the defense to adjust. To get points on the board, you then need to focus on never slowing the ball down. Every next phase or pass must be executed with speed.

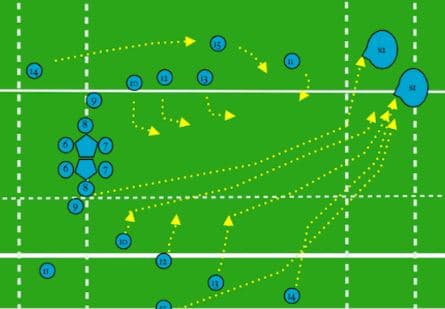

Moving the ball across the field at speed

If you can manage to move the ball across the field from one wing to a number of times, you will start to open up gaps. The gaps will come as a result of defenders over committing as the run from one side of the field to the other in cover defense.

The gaps will not open up after the first two or three phases. If you are able to keep your attacking structure and keep moving it across the field, the opposition players will start to get tired and over commit.

You will then start to get several gaps and overlaps developing across the field.

What to do on the rest of the field

If you are not defending your own line and not in the opponents 22, what should you focus on?

A lot of your decisions in this area of the field comes down to the state of the game at that time. There are however a few basic things that you should keep in mind.

The first thing you want to try and accomplish is getting your hands on the ball. This is through the same defensive principles mentioned above when defending your own goal line.

When you get the ball you need to move it closer to your opponent’s goal line as quickly and efficiently as possible. I need to point out again that a kick downfield is often not the answer, except if there is no fullback or wing in place and you have runners that will chase it.

The easiest way to move it down the field is to kick the ball with the goal to land about between the 5m line and the touchline. You then need to pressure the receiver and try to force them over the line.

Alternatively, when you have the ball you must focus on keeping it. Don’t run away from your support except if there is a huge chance of gaining a lot of meters. Play back to your supporters and steadily move it upfield by creating the mismatches and moving it from one side to the other side of the field.

Then simply rinse and repeat.

Taking into consideration the state of the game

Decision making based on the state of the game is a crucial part of a player’s rugby IQ that needs to be developed. Although the responsibility on the field will often fall on the captain or captains, each player should have a good understanding of what is supposed to happen.

The players need to be aware of the following factors when making their decisions on the field:

- how much time is left

- what is the score

- how tired are my players and the opposition players

The score is the most important consideration to take into account. It should however be looked at based on how much time is left.

Is it safe to defend the score you have? Do you need to score again? Is a try necessary or will a penalty do? How should I attack or defend based on how tired my players or the opponents are…

How to get the players to understand what you were thinking when putting together a game plan

Putting together a game plan is half the battle won. Getting your players to understand and execute it is a different story… or that is what most coaches think.

The game plan should not be discussed in fragments only during practice as players will never understand the full picture.

At the start of the season, you need to explain it to the players. This should be done in an environment like a classroom and on a whiteboard. Players should be told what you want to accomplish and then they should ask questions.

After that, you should take them out to the field and walk the field with them. Explain what should happen where so that they can visualize it a lot better.

They should then understand most of it, but it would be a good idea to revisit the whole game plan at least once or twice more before the season starts.

Then when you refer to parts of it during practice sessions, the players will know what you are talking about.